Context:

We started our journey towards Karen Barad’s “Meeting the Universe Halfway” in reading Bergson’s “Time and Free Will” (see report here). Where Bergson initially demarcated his idea of the lived experience of ‘durée’ against psychophysics, history moved it quickly to a debate between physics and philosophy. We read a report on this historical debate arguing that there was more nuance to it than the often reported ‘victory’ of Einstein over Bergson (Canales 2005). Jan Potters delved somewhat deeper in the history of this debate (see the board scheme). This brought us seamlessly to the discussion of the primacy of intuition vs. that of measurement, a theme prominent in the philosophy of Alfred N. Whitehead. Ronny Desmet introduced us to his independent reflections on this debate. This also led us to an initial comparison with Bohr’s interpretation of quantum mechanics and a reflection on the philosophical influences of Bohr (which took us back to contemporaneous discussions in a still emerging field of psychology). We will unpack this briefly below and look forward to the next session that is dedicated to Whitehead after which we head back to Bohr and Barad.

The Bergson-Einstein debate:

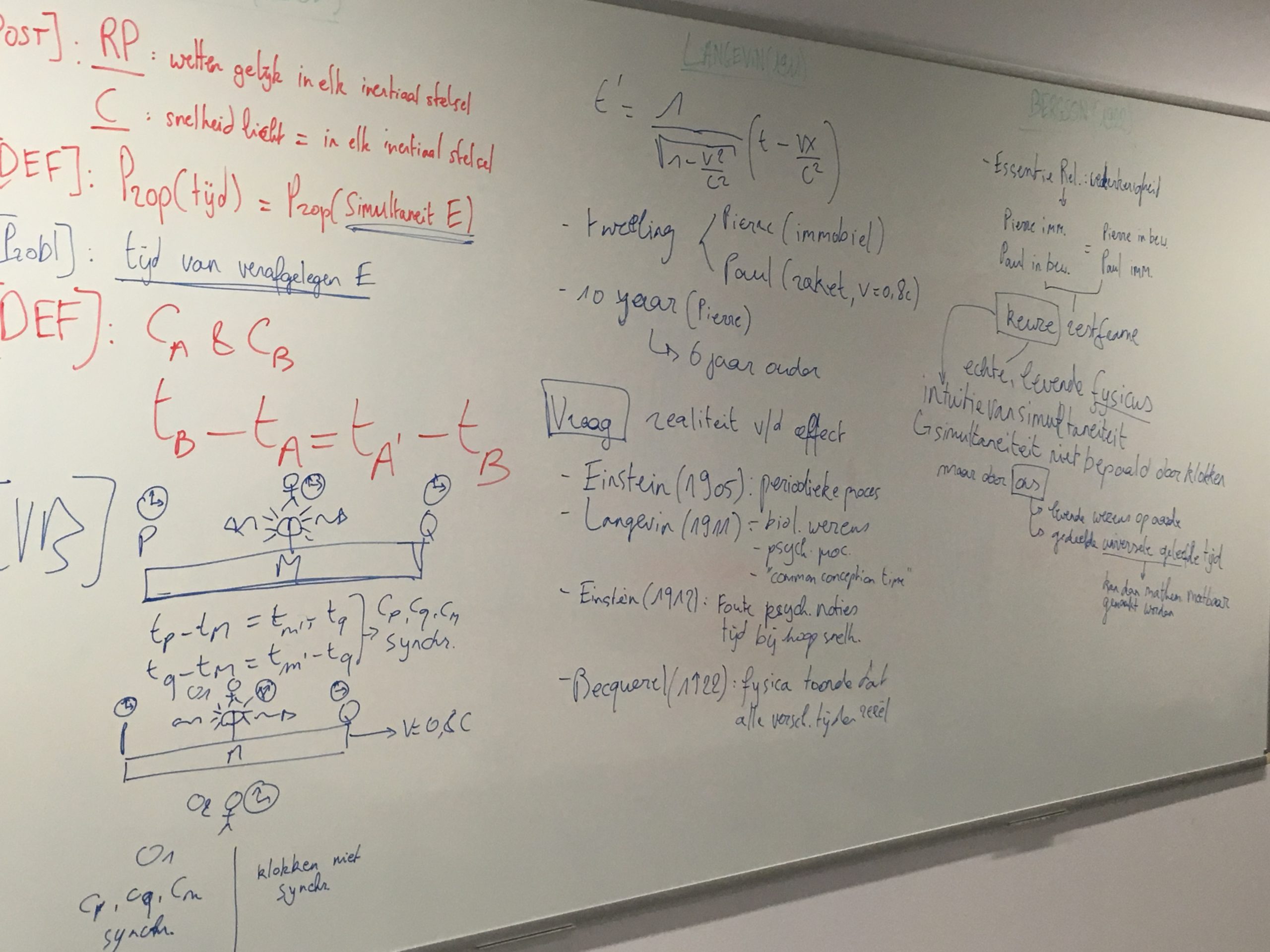

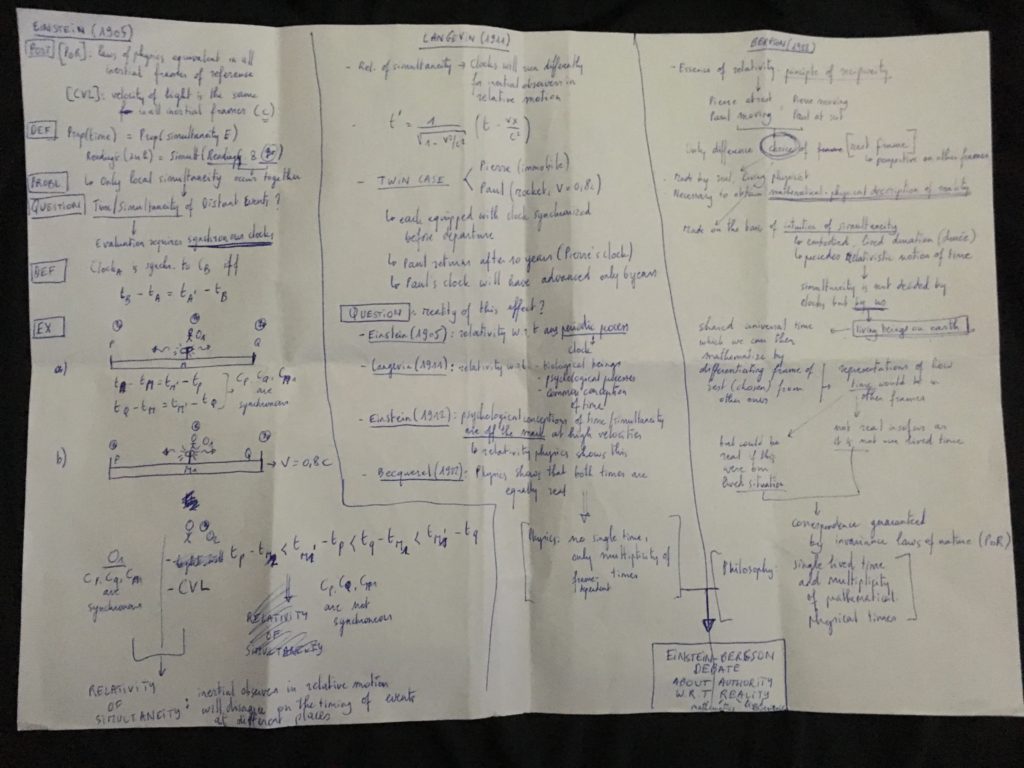

The below scheme by Jan Potters traces the genesis of this debate. Initially, left column of the scheme, Einstein sought to make sense of time and simultaneity for distant events that could not be experienced directly together. His solution, relativity of time and simultaneity, was taken by French physicists as a challenge to Bergson’s notion of the factual anchor of ‘durée’ (see middle column). At this point Bergson engaged the central ‘twin paradox’ case in this challenge to reaffirm in the face of the advance in physics his position that authority with respect to reality remained with lived experience instead of yielding to a mathematical relativization of experience (see rightmost column). We highlight the main positions based on the discussion of the ‘twin paradox’ mentioned higher.

After Einstein’s basic derivation of relativity in 1905, it was Langevin in 1911 who applied it to relativity of experience. Where Einstein’s derivation relied on the synchronicity of clocks, as paradigm example of periodic processes allowing to compare time between two inertial frames moving with respect to each other at near-lightspeed, Langevin concretized it into a thought experiment involving biological beings. After all, he argued, biological – and hence also psychological – processes were also periodic. In that case we can imagine a twin, let’s call them Pierre and Paul, where the first stays on earth and the second is launched at 0,8 light speed with a rocket. If Paul would return after 10 years (on Pierre’s clock) then Paul’s clock would have only advanced 6 years. Einstein concurred in 1912 explicitly stating that physics clearly proves that any psychological conceptions of time are off the mark at high velocities. Following that Becquerel (1922) argued that physics shows Pierre and Paul can equally claim their time is real and therefore that all experience of time is relative.

It is at this point Bergson engaged the discussion with Einstein, see (Canales 2005), as his central contention of “Time and Free Will” was challenged. Bergson also had used a Pierre and Paul thought experiment precisely to show that no mathematical-physical description of reality could challenge the basic intuition of time and simultaneity as anchored in a lived experience of durée. Here he invited the reader to imagine Pierre gathering all knowledge on Paul in order to predict Paul’s move. Bergson argued that it is clear that for Pierre to be able to do that precisely he had to become identical to Paul, in which case we could not be calling what Pierre did predicting but merely living the move Paul makes. Bergson used in the twin paradox a similar argument based on the principle of reciprocity: in order for Paul and Pierre to compare times they had to come together in the same frame of reference i.e. either one of them had to speed up or the other had to slow down. Anyway, one had finally to choose one frame as the final frame of reference from which the situation was observed by someone.

The debate then was not so much about the physics as such (Bergson never disputed the insights of Einstein as such) but about a question of final authority. Was it that, as Bergson argued, of the lived experience meaning philosophy had authority separate from physics? Or was it a question of quantitative measurement in a physico-mathematical framework, as Einstein had it, meaning physics had the ultimate authority in these questions? Or is it the same to measure the half-life of muons in two reference frames or have an actual twin that comes back together after space travel?

Enter Whitehead and Bohr:

As mentioned above Whitehead had already independently thought about the last matter. He tried to find a common ground between scientific measurement and intuitions based on experience. Part of his solution was to recognize that, even if intuition was fallible, there is in any measurement also an intuitive part: if we judge that two things are ‘as long’ then this requires us to share some experience of ‘as long’. He therefore would not agree that time is merely ‘psychologically’ relative but try to argue for a conception of time that combined a psychological and physico-mathematical aspect (a combination, see our previous section, that Bergson seems to resist). A concrete point of engagement for Whitehead is his ‘fallacy of simple location’ or of ‘misplaced concreteness’ that creates fictions of ‘isolated particles’, instead of taking relationality as basic notion.

We will delve into this in detail in our next session. Meanwhile, it is important to note that in the background of all this there were discussion in both physics and psychology critical of atomistic views. In physics Maxwell created field theories which accounted for phenomena outside the reach of mechanistic physics. In psychology, James (inspired by and inspiring Bergson) criticized associationism linking external givens to psychological states. Both will have inspired Bohr who a.o. attended lessons of Höffding taking a close look at James. So here physics and psychology come together again to inspire Bohr to take a view that kept complementarity between mechanistic and vitalist views in his, contextualist, interpretation of quantum mechanics. But now we get ahead of ourselves and will first turn to Whitehead who, in siding with relationality as basic, clearly demarcates himself from Einsteinian views regarding substances as basic.

Jo Bervoets

References:

Canales, Jimena. 2005. “Einstein, Bergson, and the Experiment That Failed: Intellectual Cooperation at the League of Nations.” MLN. https://doi.org/10.1353/mln.2006.0005.