Context:

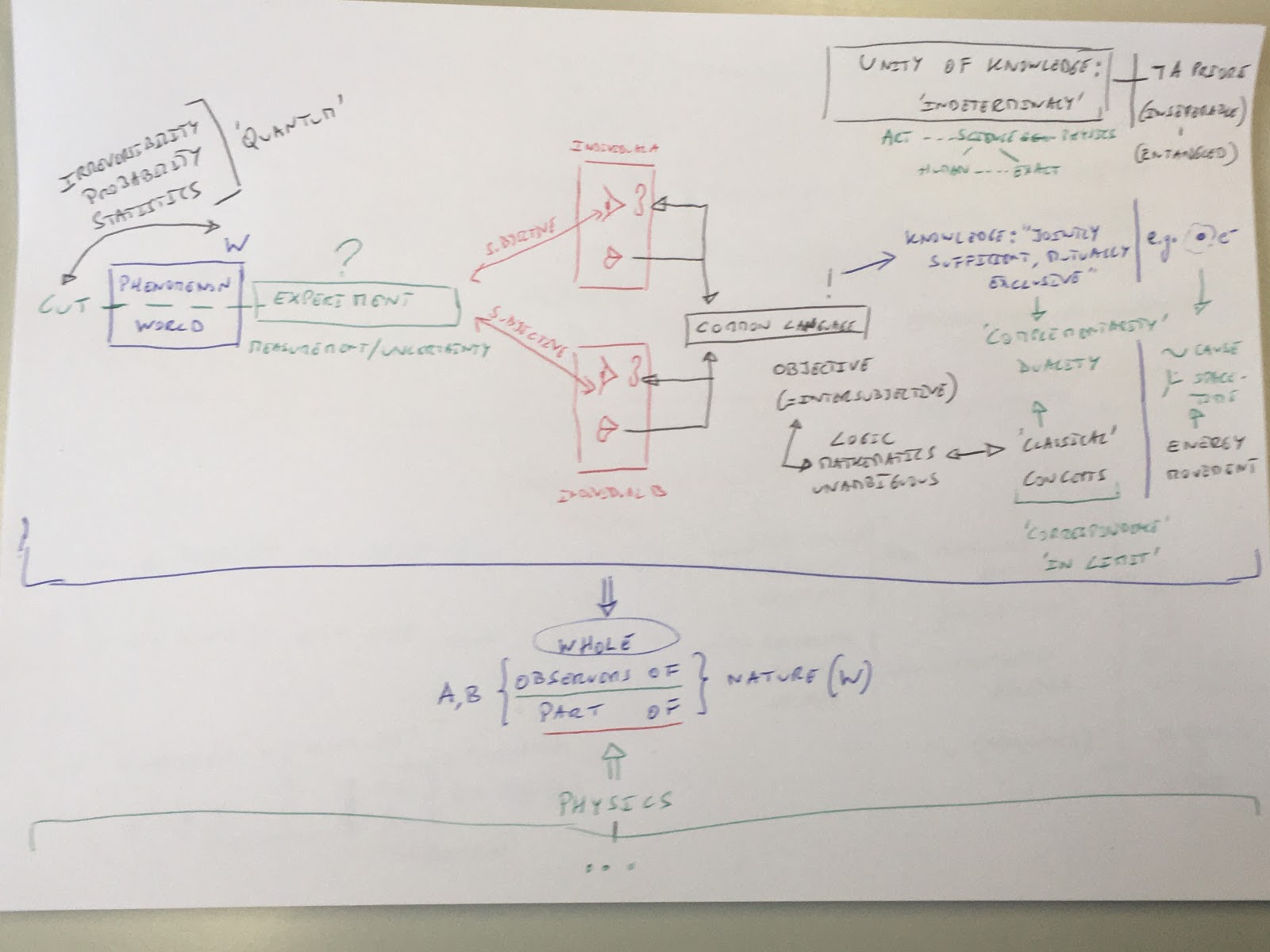

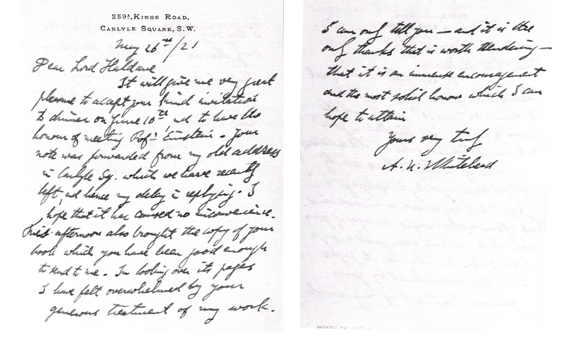

In this report we present our concluding thoughts after having read the chapters 1, 2, 5, 6 & 8 of Karen Barad’s “Meeting the Universe Halfway”. In these chapters, she explains her notion of ethico-onto-epistemology pulling together insights gained from quantum physics and the fact that our practices literally ‘matter’ (hence: New Materialism). The way we got here was in first reading Bergson’s “Time and Free Will” (see report here) to then see how Bergson’s initial challenge to psychophysics morphed into the Einstein-Bergson debate on the primacy of physics over philosophy (see report here). We then read A.N. Whitehead’s “Process and Reality” to see another principled objection to a classical-corpuscular view of mechanistic physics as the ideal scientific and philosophical view (see report here). His more holistic interpretation of the universe based on physico-mathematical interpretations (known as ‘process philosophy’) is largely ignored in contemporary analytic philosophy but serves as direct inspiration to many contemporary thinkers across scientific disciplines. Although Barad does not explicitly make reference to him, it proved worthwhile to contrast Whitehead’s thinking with that of N. Bohr (see report here). Bohr’s philosophy-physics is – for Barad – the foundation of her ethico-onto-epistemological analysis in chapters 3, 4 & 7. She argues that the epistemological lesson of Bohr needs to be extended to its ontological implications (see report here). What remains then is the link to the ethical analysis that is a fil rouge – a background motif, if you will – with all of the thinkers mentioned before. It’s also a link between quantitative insights (as in quantum physics) and qualitative insights gained from studying the lived experience (as in gender, disability and culture studies).

Barad – the conclusive:

For us there is no question Barad in fact succeeds in entangling the insights from quantum physics with those based on discursivity as discussed by Foucault and Butler’s analysis of performativity. This means that the simplistic ideas of, on the one hand, a deterministic and exact scientific view of the universe and, on the other hand, the idea of social construction ‘through-and-through’ are to be abandoned definitively. Instead, we need to accept that the actual (agential) realist view is one wherein our practices make a literal material difference. As agents or actors in this world we do not remain unmoved but, in moving, we also do not leave the world unmoved. In science we are therefore not looking for some isolated matter or some isolated practice that, on analysis, can give a definite explanation of phenomena. No, in science we’re concerned with a, necessarily indeterminate, dynamic of phenomena that produce a world in which we (humans and nonhumans) live together. While we cannot fully determine this intra-action, we are accountable for what happens since we do have a choice to exclude or include others by the practices we adopt.

Here we have added – to the epistemological and ontological dimensions discussed in our previous session – the beginning of an ethical dimension by linking the themes of quantum physical indeterminacy with the themes of (acceptance of) diversity in gender, disability as well as cultural studies. This is done by replacing the dominant exact scientific metaphor of reflection and representation by the new metaphor of diffraction and production. The latter indeed emerged from the discussion of quantum physics as an unavoidable element (this mirrors themes independently taken up by Bergson and Whitehead) in contrast to notions of exact science that, sticking with a Newtonian deterministic worldview, want to eliminate this element as a mere ‘disturbance’.

As said above, whilst we differ on whether all aspects of Barad’s analysis succeed, we do agree that the above conclusion is unavoidable: given there is unavoidably an element of entanglement or diffraction in science (as in any practice), science comes with impacts on our world that cannot be disentangled from what happens in that world. In Barad’s words – science ‘matters’ and therefore it matters what we do in science (and how we do it)..

Barad – the inconclusive:

For us there is also no question that there is more work to do on how this specifically does matter from an ethical point of view. The examples in ‘Meeting The Universe Halfway’ are, in our view, not concrete enough to provide actual guidance for instance in the field of our project: neurodevelopmental disorders.

Maybe the reason why it stays a little too abstract in connecting with ethical concerns is a consequence of laying too much focus on diffraction and disregarding the complementary aspect of reflection. Maybe (see also the discussion on humanism vs posthumanism in the previous report) this leads to a loss of connection to the typically ethical questions of doing justice to a specific other. These are interesting angles also suggested by previous reading but probably it matters less to study these angles in a very abstract way given what we’re missing is a connection to the very concrete of ethical practices in the here and now or the you and me. At least in our discussion, we spontaneously geared towards the question of how science matters and, in light of the above, what a good scientific practice is.

A call for intra-action:

So, we end this reading club with a desire to produce something that builds on the reading we have done: a way to argue that – contrary to the received opinion in the modern West – science without experience is simply unscientific. This probably requires us to make more precise how quantitative and qualitative methods combine to form good science (maybe in the way that Oliver Sacks’ efforts to give people with a neurodevelopmental disorder their own voice was critical in unleashing scientific advance in this field). We believe this would be a worthwhile bridge between New Materialism and more conventional views of science and ethics, an intra-action bringing scientists and scholars in the different disciplines closer instead of digging ever deeper terminological trenches.