About half a year ago I, Lisanne Meinen, joined the NeuroEpigenEthics team. I am working on an interdisciplinary PhD project that studies the depiction of psychiatric diagnoses (autism, depression, psychosis) in video games. In this blog post, I will explain my research and tell something about my plans for the upcoming years.

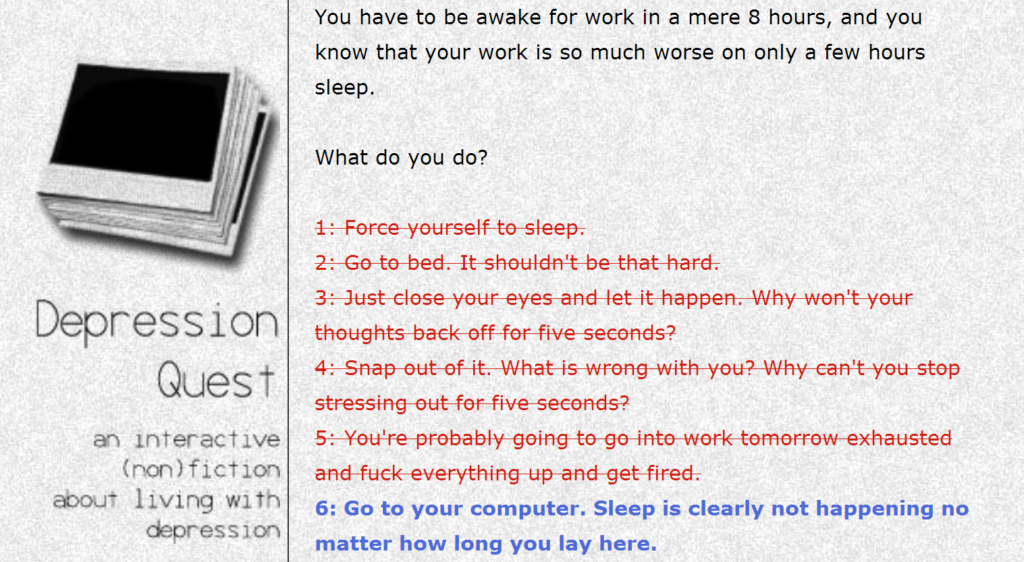

In my research, I examine how the psychiatric conditions autism, depression, and psychosis are represented in both commercial and ‘indie’ video games. I look at thematic representation, for example through the inclusion of a character with autism such as Symmetra in the RPG Overwatch. Additionally, I analyze how these psychiatric conditions are woven into the rules and structure of a game, as happens in Zoë Quinn’s autobiographical Depression Quest.

In addition, I study how interpreting games critically and ‘playing’ them against the grain can deconstruct and challenge societal prejudices and norms surrounding, for example, healthy bodies and sane minds. Such approaches are important if we want to look beyond just diagnosing game characters or looking for certain symptoms. Ultimately, I want to see how psychiatric diagnoses are incorporated into games—both from the designer’s point of view and from the game itself—but also how that affects the player’s gaming experience.

The character Symmetra in Overwatch

Currently, video games and psychiatric conditions are almost exclusively linked in research with an instrumental (usually therapeutic or educational) approach. Therapeutic studies focus on the potential of ‘gamification’ or ‘serious games’ to control or reduce certain symptoms. In such a case, the video game is used instrumentally and the focus is mainly on the diagnosis and not on the person behind it with all their feelings, thoughts, and experiences.

In the case of an educational approach, video games are seen as a unique means of increasing people’s understanding of certain psychiatric conditions and thus countering stigma. While this is a noble motivation, it also invites some criticism. For example, simulations of a certain psychiatric condition can actually encourage stigmatization. In addition, while the aim of these video games is often to elicit empathy, the term is all too quickly used as a buzzword. It is important to be specific about what is meant by empathy: what kind of emotions does a game evoke exactly?

To question this instrumental approach as a norm, I focus on games designed primarily for entertainment purposes. In doing so, I look with an open mind at the different ways in which a video game can be played, and thus at the different ways and meanings of an enjoyable gaming experience. I want to explicitly take a non-medical approach to autism, depression, and psychosis because I find the medical view too limiting. In this line, insights from fields such as crip studies and neurodiversity studies help me to be critical of dominant societal norms about ‘healthy’ or normal’ minds.

In my research I continually work in two directions. On the one hand, I want to know how our thinking about (dis)abled bodyminds in fields like disability studies can contribute to a more nuanced and better representation of autism, depression, and psychosis (and the experiences of those diagnosed with them) in video games. On the other hand, I want to think from the perspective of video games themselves and study how nuanced games can contribute to broadening the conceptualization of psychiatric diagnoses as dynamic and changeable. Because playing a video game is an interactive affair, all these different sides can be well illuminated.

The interactive autobiographical game Depression Quest

In all these approaches, I cannot do without the insights and ideas of people with lived experience with autism, psychosis, and depression. Therefore, in different ways in my research, I will actively collaborate with people who have a diagnosis themselves. For example, when I interview game designers who have incorporated their experiences with a particular diagnosis into a game. Or when I question people with a diagnosis about their experience when they play a game designed to be about them. Is it alienating to play a game about yourself, does it make you angry, or do you find recognition in it?

Ultimately, then, we can learn a lot from video games, but presumably not in the straightforward way that designers of educational games have envisioned. Instead of games aimed at identification, what we need above all are more games that teach people to respect those who are different from them. With my research project, I hope to define what such video games would look like.